I came across an interesting article by Alan Boyle tonight that could work well in my Critical Thinking class.

Apparently, Alan Stern is NASA's lead man on Pluto, and he says that the new definition on planets by the IAU shouldn't be bowed to so quickly. "Many people just refuse to use the IAU definition," he explains. "Although a lot of teachers think the IAU [decision] is a done deal, people are slowly coming to realize, 'Not so fast.'"

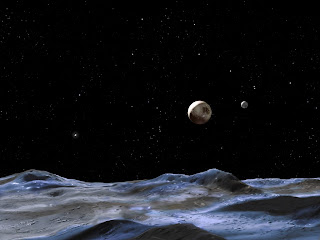

When it was discovered that Eris and Ceres were even more distant small, icy planets, a choice had to be made. We could add to the list of planets, or classify Eris and Ceres as something else. But if Eris and Ceres aren't quite "true" planets, then is Pluto? The IAU decided that it is not. It would be better to say that our solar system has eight planets, and several dwarf planets, or planetoids, beyond those eight.

One aspect of their definition that has caused trouble is that it is said that a true planet must have "cleared the neighborhood of its orbit." But many have argued that if this is so, Jupiter might be argued to not be a planet, because of the asteroids in its orbit.

The point to be made for critical thinkers is that the definitions at the base of our arguments are a tricky business. It is sometimes difficult to say exactly what something is. Augustine, in the 11th book of his Confessions says he knows what 'time' is until someone asks him to define it. Then it gets problematic. The same could be said for planets. The same could be said for a 'person'. And as anyone who has spent much time on ethical issues knows, defining a 'person' makes all the difference in the world to many debates, not the least of which is the abortion question.

One of the important philosophical questions is what we expect to get out of a definition. Some of us believe that we're trying to say what something really is in itself. From a naive point of view, that seems obvious. From the point of view of philosophical training, it takes a little bit of nerve to argue the case.

One way of dealing with the problem raised by skeptics, who insist that we can't really know anything about the world as it is in itself, is the pragmatic solution. That's raised by Stern in this article. As Boyle writes, "Stern trusts that the scientific debate will eventually settle on the right answer - about Pluto, and about the worlds to come." Stern expresses the pragmatic point of view quite succinctly when he says, "Things that don't work fall by the wayside. Things that do work are the ones that we keep."

I am something of a pragmatist. I believe that some statements have more "cash value" as James put it than others. But pragmatism divides into two schools of thought: roughly the difference between William James and Charles Peirce. James seems not to have thought we could get at the truth. Peirce believed that we could, and certainly believed that the scientific enterprise is about trying to get it right. The former view is nominalistic. The latter is realistic. Peirce believed that much that had gone wrong in philosophy was due to nominalism. Nominalism is the view that our concepts are just names we give to things. On that view, we can call whatever we want a planet, and the only question is what works for us. It's up to us what a planet is, and what it is not. Peirce, like Stern, would have said that scientists will eventually "get it right." That's a realist's expectation. I agree with Peirce and Stern.

But it's not easy to see why nominalism isn't true. Is there any way to tell that the IAU's definition is right, and that its critics are wrong? Is there any way to tell that the critics are right and that the IAU is wrong? We'll have to wait and see. The reason pointed to above suggests that an inconsistency may shoot the IAU's definition down, unless they're willing to reclassify Jupiter as well.

What is a person? Can a machine be a person? Can a robot be a person? Can an animal be a person? Can a fetus be a person? Can we know the answer to these questions? Or is it a matter of whatever works for us?

What is God? How we answer that may go a long way toward determining whether we consider ourselves to be atheists or theists. If I had to accept the traditional definition of God, I'd probably have to agree with the critics who say that such a being can't exist. Can a perfect being create an imperfect world? No. Do we live in an imperfect world? I'd have to say that we do. But I have an experience of a power that I could call "the force" from having watched too many Star Wars films enthusiastically. I have an experience of what I could call "chi." And given the modifications I've made to the concepts that were taught to me about God from the Judeo-Christian heritage of my childhood, I still believe that there is an intelligent source behind this power that flows through everything. But not only is that source not a man with a grey beard resembling a cosmic Gandalf, but that source is not perfectly omnipotent or omniscient. The world is in flux, and my "God" doesn't coerce. It persuades. And that's all my God can do. It is limited in what it can do: in the illusory world of our everyday experience.

Is such an intelligent source worthy of the name "God"? Is it possible I should just give up on such a term? I personally believe that this source is worthy of our devotion. And I believe that the traditional God who would be personally responsible for all the devastation that the world has ever seen, including the Holocaust, is not worthy of devotion. From my point of view, if there is such a being that is worthy of devotion, then it deserves to be called "God." But I'm more of a stickler about the concept than the word. You can call it whatever you wish. If it's an intelligent source behind this life force that we feel, then we're in agreement, whether we call it the Tao, or Brahman, or Allah, the Absolute, or whatever.

But you see that our deductive arguments depend ultimately on premises that conclusions are deduced from. And our premises only have the power they do because they use concepts with agreed-upon definitions. And coming to such agreed-upon definitions can be a very tricky business indeed.

No comments:

Post a Comment