In a recent article from the Manhattan Institute (July 17), Paul Howard writes "A Story Michael Moore Didn't Tell." Moore's stories in the movie "Sicko" reveal the weaknesses of the American health care system, and the strengths of the systems in Canada, Great Britain, and France. Howard writes about basketball star Derek Fisher's daughter, Tatum, and her bout with retinoblastoma, a rare form of eye cancer.

Howard writes: "Tatum's story is a microcosm of how the United States is revolutionizing cancer treatment. After her diagnosis, Fisher and his family flew Tatum to the world-renowned Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, where doctors are testing an experimental procedure that didn't exist even a year ago. At Sloan-Kettering, Dr. David Abramson and his colleague Dr. Pierre Gobin enrolled Tatum in a clinical trial where cancer-killing drugs are injected directly into the eye in an attempt to not only kill the tumor, but to save a child's eyesight. After treatment, Tatum's doctors were optimistic that her prognosis is good."

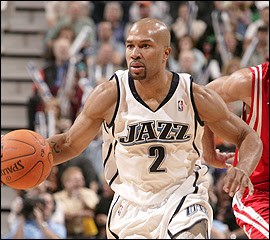

It's a wonderful story, and I was watching the basketball game when Fisher returned to the line-up with the Utah Jazz. I applaud our researchers, doctors, and Fisher's commitment to his daughter's health.

Howard's point in the article is that the free market incentives that we have in the United States are what is driving our research in areas such as cancer, and we are, without a doubt, a world leader in such research. He points out that in Europe, such treatments often are delayed due to negotiations with the government over prices. As a result, most launches of new drugs occur first in the United States.

The moral of the story, for Howard, is that we ought to celebrate the great system that we have here in the United States, and stick to a free market system rather than what conservative ideologues will disdainfully call the "socialist" system. But the point is lost on me, I'm afraid.

First, I'm glad that Derek Fisher, who makes millions of dollars a year to put a round ball through a hoop, can afford to fly his daughter into New York for the best treatment in the world. But how many people can afford that kind of care? I have no problem with some semblance of a free market existing for those who can afford the best care that money can buy. But what about the rest of us? I am not persuaded by this story, or statistics about first launches by companies that care more about making money than helping people, that we should continue to have an unregulated system where many of us are uninsured or underinsured. I am not persuaded that we are better off than the people of Canada, Great Britain, Germany, or France. Perhaps France would not have to haggle about price so much with these companies if the United States also regulated the prices of health care. One of their problems is that the U.S. provides a place to get rich quick without regard for the needs of the average citizen who couldn't afford such care.

Eventually, these other countries will have the same treatments available. The rich may just have to wait to get them.

As a philosopher, I look at this problem, and can't help but wonder why researchers can't work toward a cure for cancer without the promise of getting rich in the process. In Tolkien's The Hobbit, Bilbo refuses hordes of gold because he wonders what anyone like him could do with it all anyway. He accepts a modest reward instead. Most researchers are like Bilbo. They do their work for modest rewards. It's the corporations that thirst for gold. I'm all for the government regulating it, and having a system where we all have the basic health care that we need.

No comments:

Post a Comment