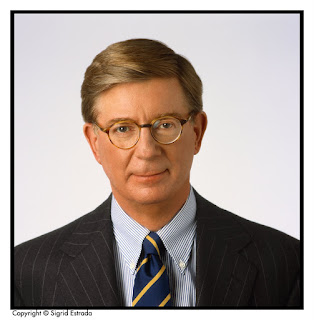

Sometimes I wonder what got into my head when I was a very young man and came under the influence of the pen of George F. Will. And then there are days like today when I read his column, and know exactly why I came under his influence. Today's column is entitled "Contempt of Courts," and Will demonstrates yet again why he is such an important political writer. He is a rare breed of conservative today: he actually puts reasoning ahead of partisanship.

John McCain has called the decision by the Supreme Court to prevent the executive branch of our government from unilaterally holding prisoners at Guantanamo Bay without so much as filing charges against them (let alone making the case) "one of the worst decisions in the history of this country." Will lists a whole series of cases, including the Dred Scott decision that supported slavery and took away all rights from African Americans, and wonders if McCain really things it is in the same league with those. He suggests that McCain's comments were not so much about the case as they were a political tactic bent on making the Supreme Court balance an issue in the campaign. Will writes:

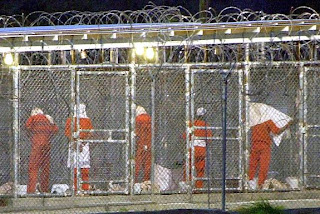

The purpose of a writ of habeas corpus is to cause a government to release a prisoner or show through due process why the prisoner should be held. Of Guantanamo's approximately 270 detainees, many certainly are dangerous "enemy combatants." Some probably are not. None will be released by the court's decision, which does not even guarantee a right to a hearing. Rather, it guarantees only a right to request a hearing. Courts retain considerable discretion regarding such requests. As such, the Supreme Court's ruling only begins marking a boundary against government's otherwise boundless power to detain people indefinitely, treating Guantanamo as (in Barack Obama's characterization) "a legal black hole." And public habeas hearings might benefit the Bush administration by reminding Americans how bad its worst enemies are.

Will is far more gracious to the far right's response to this decision than I would be. He says that it is something reasonable people can disagree about. He admits that there is merit to Chief Justice Roberts' concerns that the decision creates more ambiguity than clarity. For example, does this decision mean that while the Bush Administration can't run concentration camps at Guantanamo, it can run secret prisons around the world in areas completely outside of U.S. jurisdiction? Does this decision mean that other Constitutional rights also apply to the prisoners at Guantanamo?

I wish that I believed that these clever arguments were the main reasons Roberts disagreed with the decision. I wish I did not believe that he is another vicious right winger whose main concern in life is for security, survival, and victory rather than for justice. But I admire Will's attempt to show the virtues of the right wing Justices' reasoning. I admire more his ability to get to the heart of the matter when he writes:

No state power is more fearsome than the power to imprison. Hence the habeas right has been at the heart of the centuries-long struggle to constrain governments, a struggle in which the greatest event was the writing of America's Constitution, which limits Congress's power to revoke habeas corpus to periods of rebellion or invasion. Is it, as McCain suggests, indefensible to conclude that Congress exceeded its authority when, with the Military Commissions Act (2006), it withdrew any federal court jurisdiction over the detainees' habeas claims? As the conservative and libertarian Cato Institute argued in its amicus brief in support of the petitioning detainees, habeas, in the context of U.S. constitutional law, "is a separation of powers principle" involving the judicial and executive branches. The latter cannot be the only judge of its own judgment. In Marbury v. Madison (1803), which launched and validated judicial supervision of America's democratic government, Chief Justice John Marshall asked: "To what purpose are powers limited, and to what purpose is that limitation committed to writing, if these limits may, at any time, be passed by those intended to be restrained?" Those are pertinent questions for McCain, who aspires to take the presidential oath to defend the Constitution.

If only Marshall were back at the head of the Supreme Court, I might have more confidence that justice will prevail in our country.